Bow Performance Project - Simsek Turkish and YMG Korean

Silent Thunder Ordnance

It has been far too long since we updated this project. So on the review block today are two bows, a Simsek Turkish Hybrid+ and a YMG.

Simsek is a Turkish manufacturer of all-resin (non-laminated) Turkish style bows. They’re going through something of a surge in popularity at the moment. They have sinuous curves, and are one of very few Turkish designs out there which, at a slight distance, could pass for an authentic horn-sinew composite unstrung, strung, and at full draw. They also offer painting or tezhip, to further beautify their bows. A lot of manufacturers show pictures of bows so decorated, but actually ordering one with it is another thing. With Simsek, it is a standard option. It all comes together to form a package which is probably one of, if not the best looking Turkish style bows on the market.

For those who don’t already know, a quick primer on bow technology. Most of the bows out there are laminated, meaning the working parts of the limbs are formed by pressing and bonding dissimilar materials together, ones strong in tension for the back, strong in compression for the belly, and light weight and shear-resistant for the core. This minimizes limb mass and increases bow performance, but is more expensive to do and very broadly speaking tends to be less durable. Laminations on bows tend to fail at the glue joints, and so they are a common failure point. Examples of laminated bows include original horn-sinew-wood composites all these bows are based on, the YMG we’re testing below, and the AF Archery bows we’ve tested before. All resin bows are not “laminated” per se. The working part of their limbs, or in some cases the whole bow like this Simsek, are made of a single piece of material usually cast, extruded, pultruded, injected, or or in some cases laid up manually. It is still a composite material, a blend of resin and some other material to increase strength typically fiberglass, but the cross section of the limb is essentially the same density throughout. In the case of Simsek, the bow is likely made by placing strips of fiberglass or carbon fiber cloth into a mould and painting resin on, adding more and more until the mould is full. The primary advantages to this are much lower manufacturing cost and much better durability. However this comes with a major design challenge, which is increased limb mass that in turn results in slower speeds, lower efficiency, and handshock. The Simsek weighs 336 grams, which is actually quite light. The bow itself is physically very small and slim. Compare that to the bigger bulkier Grozer, of similar poundage, which is a more portly 530 grams. Three examples of “resin” bows we tested were the Elong Yuan (retracted; bow is not recommended), Grozer Turkish, and JZW Manchu. All three were notable for their comparatively lower efficiency, although in the case of the Manchu, high efficiency is already not expected and much of the limb mass is in the siyahs rather than the resin working limbs anyway. It will be very interesting to compare the Grozer to the Simsek as they are so similar in style, design, and construction. I digress.

ref. Simsek Bows 2020

In shooting, the Simsek draws draws with remarkable smoothness for such a short bow. Keep in mind, strung, this bow is 43” tip to tip yet boasts a 32” maximum draw. It is only a little bit longer than the arrow itself. It also draws quietly, without nock creak or leather squeak. Arrows head down range straight with little effort on the part of the shooter, and with what seems like real urgency. The grip is slight, delicate in the hand, just enough to hold onto. More than any other bow I’ve shot, you really feel the draw weight in your grip hand. There is a slight almost metallic “clink” as the string comes taught at the base of the siyahs, with no residual vibration. There is hand shock, as there is with all bows due to the residual energy needing to go somewhere, however the perception of it is likely greater than the reality, simply because the grip is so slender and the bow appears to waste little mass to the grip section. It really has great dynamics and is a pleasure to shoot. I’m guessing it will buck the trend for efficiency.

Base price is about 420$ for the Hybrid S delivered (to the United States, at time of writing), however that is before you dive into the options list which can start to make your head spin. Want leather covering on your Simsek Hybrid? That is another 60$. Want more than ~40-45 pounds draw? Add another ~60$ for every 5 pounds draw all the way up to “+100#s.” Want decorative panting called Tezhip? Add another 110$. Want to jump to the shorter, and presumably faster, Sipahi and you’ll have to add another 170$. So, as you can see, the price can climb quite steeply here with options. Simsek noted in a post on their facebook page that they can build 250# bows. This is huge. Very few companies sell war weight bows at all, and a lot of this has to do with the failure rate. Simsek’s willingness to make such powerful bows could be seen as a testament to the design’s durability. We opted for a Hybrid S+ with tezhip specified for 41-45#s. After all, if the shape of the bow is to be beautiful, why not the rest of it? For this we paid a total of 540$, which included a 10% promotional discount from another reviewer (thank you Armin Hirmer, if you are not subscribed to his youtube channel, you should be), without which the price would have been about 600$.

This price, much of it paid for aesthetic features, lends itself to a little closer scrutiny of the bow. Overall the bow is exquisite. There are a lot of very beautiful details. It is slender, almost dainty, in character. Limbs are deliberately thin, presumably for efficiency and so are the siyahs. It is curvaceous in all the right ways and places. It really is one of, if not the only, Turkish style bow which looks like it could be a horn bow both unstrung, strung, and at full draw. The belly also appears to use a different color resin from the siyahs so the former looks more like horn while the latter looks more like wood.The painting was also beautifully executed. And now we get to my only negatives about the bow. It falters somewhat in a handful of flaws visible on closer inspection, bubbles on the belly, rasp marks/rough finish scattered around the bow, and a little fiberglass poking out of one of the siyahs. On a base model these don’t affect function and would hardly bear mentioning, but on a highly decorated bow one would display, they aren’t particularly desirable. There are two other things to note as well. There are a couple sharp edges around the nocks, and where the string contacts the belly, and after just a few shooting sessions the serving had started to fray. These can be relatively easily remedied by the user, but are worth noting. And, more worryingly, after testing was completed a splinter appeared on the belly. Another shooting session saw that splinter grow, and so for safety reasons use of the bow had to be discontinued. We chatted with Simsek about all this, and they determined that this was not expected from the bow and they plan to replace it. We’ll update this review when the replacement arrives. *update the replacement arrived 9.9.20, in the form of a new Tatar style bow. We’re in the process of evaluating it now. That will become a new blog post when completed.* I should note here that Simsek were great to deal with. It is important to understand that bows exist with very little margin for error, or what is called “safety factor” in engineering. That is to say they innately exist very close to the edge, and are there deliberately as it improves bow performance. This means that, irrespective of quality or brand, there will be a certain failure rate. So one must not judge harshly any single bow failure, especially as the bowyer was happy to replace it. Below is a gallery showing these issues. As you can see, all require closer inspection to notice.

But looks are nothing without performance, so how does this bow perform? There is unfortunately relatively little data out there on the subject, and what is available can be a bit confusing. Take draw length as a case in point. On Simsek’s website they have this to say:

“We make our tests and measurements at 28″ standards, So our recommended Draw Length is 28″. But Draw Length is within safety tolerances in 28″~30″ range. Maximum Draw Length is 32″.” Meanwhile their pictograms, as shown a bit further up the post, indicate 28-30” max 32”.

What does all that mean, exactly, and as a tester what are you to take away from it? I would expect it means the bow begins to stack in the 28-30” range, what it was optimized for, however can still safely be drawn to 32”. The plan then is to test this bow at the same 31” draw length and using a thumb ring as we do with all our other tests as it is within the range provided by Simsek. To sacrifice draw length would put the bow at significant performance disadvantage. Additionally, finger draws act like a longer draw length by about an inch and a half at this extreme string angle as you have a larger string displacement. Using a ring, which we obviously do, gives you a little more room to draw as compared to what manufacturers tend to advertise.

We chatted with Simsek a bit on the subject of performance as well. They provided two examples of other performance tests. First was a post by Ivar Malde, an accomplished horn bowyer and flight shooter. A quick summary was that bow produced 46#s at 27” draw, and produced 258fps using a 200 grain arrow or 4.3gpp. The associated picture indicated this was done on a mounted flight shooting rig, with an overdraw device, and I presume was a peak measurement as is typical of flight bow tests. Simsek noted that this was also a special bow made for the purpose, not a standard model. The second example was from Dr. Murat and was much more comprehensive, albeit in Turkish. The data is still in the “universal” Arabic numerals though, and indicate that the bows are about 65% efficient at 8gpp and approaching 70% efficient at 10gpp. The produced velocities of about 170 to 190 FPS again at 8-10gpp. This is roughly comparable performance to Czaba Grozer’s all resin Turkish bow, however Simsek again added the caveat that the design has been updated (twice) since then and the performance should be better still. The most recent review by Armin Hirmer was a bit more casual, but again indicates performance is in the 170-180ish FPS region which is roughly in line with that of Dr. Murat.

We’re no stranger to YMG bows here. We’ve tested two before in this series, this makes the third. So why is this here, why three? Simple: it is a personal bow, picked up for recreational uses, and as we’re doing testing on the Simsek why not simply include it? So we’ll breeze through this bow a little quicker as we’ve already covered the subject, but for those unfamiliar, YMG bows are available under a variety of brands now, and no wonder: they are reasonably priced, durable, have exceptional performance, are available in war-weights, and are very very beautiful. I went out and purchased this bow with my own money for my own personal use purely because I love them. They are quiet shooters, smooth drawing, and are truly, properly, fast. They are also very authentic looking, having curved and polished synthetic on the belly which looks like horn, rounded edges which look a bit like the mounding of sinew, and are covered in natural beautiful birch bark. Both strung and at full draw it takes an experienced eye or closer inspection to tell them from a horn-sinew composite. Replacing the rubber strike pads with leather is a quick and easy way to take it even further. Grip wrapping varies and options range from scouring pad material to dimpled rubber to various leathers. It is easy to redo, however in this case I stuck with my preferred dimpled rubber which provides a strong and comfortable low-wrist grip, a nod to practicality over authenticity. Perhaps some day I’ll replace it with a highly textured exotic leather of some sort. This grip texturing is very much necessary by the way, as these Korean bows require active archers. While the Simsek above effortlessly spits arrows straight, these Korean bows make you work for every shot. Get your form right and you will be rewarded with beautiful straight arrow flight with incredible smoothness and speed. Get it wrong and you can find your arrows wildly fishtailing and wide of the mark. These bows really are shooters, and that is why I shoot a YMG more than all the other bows we have combined. Oh and did I mention they’re available in war weights? (see our previous tests) I do dearly love these bows, and this one has been no exception. Having shot this YMG a fair bit before this test, I’m not expecting it to disappoint in the performance category either. Total price paid for this bow was 380$ delivered to the United States. This makes it more expensive than most of the Chinese made laminate bows and entry level Korean bows, but less expensive than many of the “special” Korean bows most of the American or European made laminated bows.

As I have three essentially identical bows here, I want to take another brief digression and talk about lamination and the power of composites. As you can see from the chart below, at a draw length of 31” they are 106, 71, and 52#s respectively. That is quite significant. What about differences in mass though? Putting all three on a precision gram scale, without their strings, I got masses of 362, 353, 347g respectively. That is HUGE. The most powerful has twice the draw force and stores twice the energy but has almost identical moving mass. And all that comes down to bow construction. I strongly suspect the material, likely glass and carbon fiber, laminated to form the back and belly of these bows is the same for all poundages. The only difference, as far as draw weight is concerned, is the thickness of the wood core. That slightly thicker wood core places the primary load bearing laminations further from the neutral plane and so they do more work. This means that, for equal gpp projectiles, the higher draw weight bows will be more efficient. Conversely, it means this YMG should be the least efficient of the three I own. How exactly that will play out given that arrow mass remains constant is harder to say.

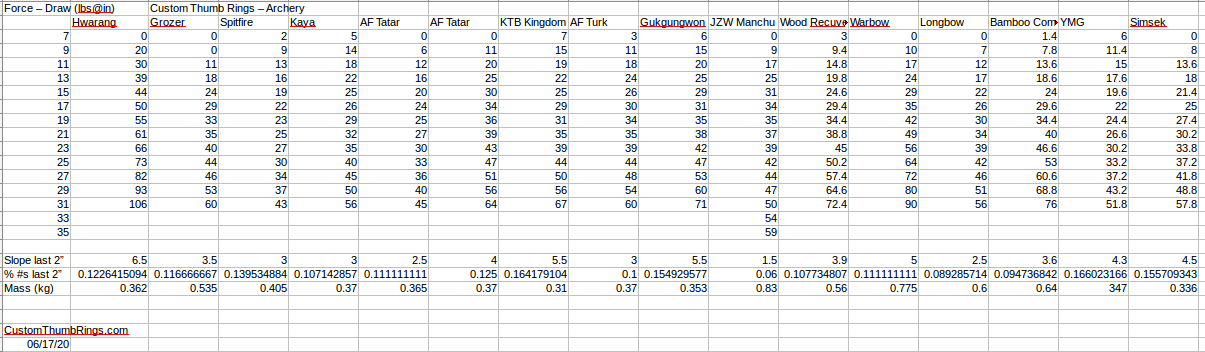

Force Draw Data

Here the Simsek is at a disadvantage, as are all Turkish style bows. Favoring both a shorter optimal draw length and a higher brace height, these bows just tend to store less energy and stack more in these tests. That is no fault of Simsek’s, just part of the style. And it does come with its advantages. If you’re optimizing for shooting very light arrows very fast, a shorter arrow of equal cross section will have both less mass and a higher spine. Stiffer means the projectile can be further thinned, and lighter arrows require less spine. In short it is a feedback loop which can significantly reduce arrow mass. Higher brace heights and that thin grip are also major contributing factors to why the Simek effortlessly produces beautiful arrow flights while the YMG makes you work for it. The Simsek clearly would prefer to be drawn about 28” but even at 31 it is still performing admirably with a slope for the last 2” of just 4.5 and gaining just 16% of its total poundage there. Not bad at all for such a small bow. I should note here that the entire draw stayed relatively linear before the stacking kicked in. More reflex and a more aggressive siyah angle could change this, increasing the pre-tension (early draw weight) and further flattening the middle of the draw curve, but would also further stress an already extreme bow design.

The YMG was, somewhat surprisingly, in the same ballpark as the Simsek starting to stack a little at the end with a slope of 4.3 and gaining 17% of its total poundage in the last 2”. “Ideal,” if you consider a bow with a linear draw ideal, would be 6-7% of total poundage gained in the last 2”, although of course the JZW Manchu is the only one which manages it. This is a somewhat dismaying performance for the YMG, I would have expected it to be smoother, as it sure feels it.

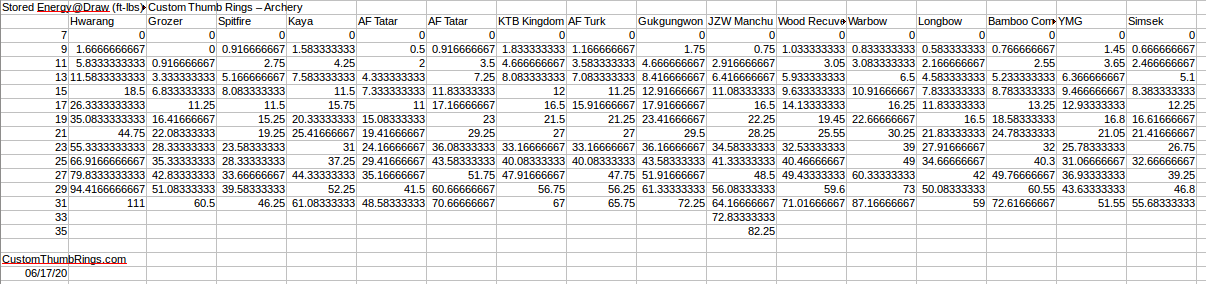

Stored Energy

This is an interesting metric, total stored energy at a given draw length, and illustrates well why I decided to push the Simsek a full inch beyond its “recommended” draw length. Almost 20% of its total stored energy comes from those last 2”. It actually stores more energy than the YMG next to it, despite a late start (higher brace height) and the same nominal poundage (45#s at 28”)

Stored Energy/Poundage

Here is where the playing field gets leveled and bows of vastly differing poundage can compete on a level field. For those unaware of how this works, you essentially divide the chart one section above (energy stored) by the first chart (draw weight at length). The result is that bows of dissimilar draw weights can be compared on equal footing, and the question of how efficiently they store energy can be answered. Both the Simsek and YMG end up toward the bottom of the pack here. The Simsek has all the aforementioned excuses, while the YMG does not. The Simsek was doing quite well until it passes 27,” again a nod to Simsek for knowing what they’re talking about and their bow performing basically as advertised. It is only after that point that the stacking begins and curve flattens out. The YMG does better, and is technically within margin of error of 1.0, my “standard” if you will, but for a bow designed for the long Korean draw which in some cases runs out to 34” this was less than stellar. I should mention again that the Simsek is several inches shorter than the YMG here. More surprising though is that the Grozer, about the same length and with even more extreme reflex unstrung, did almost 5% better. That I did not see coming. I’m not making comparisons to the AF Turk here simply because that bow is more of a homage to the Turkish style more than it is a real “turkish style” bow. It possesses a greater length, less reflex, lower brace height, and was clearly designed for a longer draw.

Chrono Work

And finally, here we are, where the rubber meets the road. How does it sling an arrow? Well the YMG managed a respectable 180fps average and a respectable 70% efficiency. I also have to say, this is where the Simsek genuinely surprised me, managing a 70% efficiency as well. That is good by any standard, but for an all resin bow that is surprisingly good. Contrast that with the Grozer’s 64% efficiency, the best comparison as another leather covered all-resin bow, and you can really see the magnitude of what Simsek accomplished here. All this was accomplished at 8.7gpp. These numbers are roughly in line with Dr. Murat’s above, although it appears Simsek did indeed find a little more efficiency somewhere.

There is one other thing worth mentioning here. The Crimean Tatar style of bow has a history of being manufactured by Turkish bowyers. This traces back to the Tatars being used by the Ottoman military, thus they needed to be able to equip them. (for those unaware, war is a largely logistical institution) If I might be so bold, Simsek could bring this tradition forward and produce their own interpretation of the Tatar style bow. It is a style which has great performance potential, but is a little less extreme than the Turkish style having a more generous grip and longer draw. If Simsek can work their high performance all-resin magic on that style of bow, they may well make a winner which appeals to an even broader audience than their Turkish style. After all, many other military horn bows find themselves similar to the Tatar style. Just a thought.

Thanks everyone for reading. I hope this throws a little more light on the mechanical performance of bows and their design.