THE STABLE

-Hwarang - Supplied by Thomas Duvernay, these bows are absolute gems.

-Grozer Turkish - Csaba Grozer requires little introduction. This is a Turkish base bow from several years ago now. To my knowledge, this bow has some of the most extreme reflex of all modern reproductions.

-Spitfire - Made by Chris Constantine of Spitfire Horsebows, this carbon fiber bow is also a few years old now but no less snappy. It is also nicely decorated.

-Kaya - A maker of popular and inexpensive Korean style bows, this example is decorated in paisley patterned leather.

-AF Tatar - AF archery is a, relatively, new player on the market. With beautifully made and inexpensive Saluki-style bows (Saluki style in that they're laminated and left exposed rather than wrapped) I suspect they'll rapidly grow in popularity. Many of their new designs have also grown in price to compete with the more expensive laminated Alibow offerings. Thus far, these have been cracking fast too.

-KTB Kingdom - Another of the carbon Korean wunderbows, this time for sale at Freddie Archery, these are advertised with poundage at 31" and no max draw length. Somewhat surprising then how this bow begins to stack as 31" is approached, as it is smooth up until that point. It also, like the Hwarang, has a beautiful convex belly. A very practical bow, and a favorite of mine to shoot.

-AF Turk - This is one of the more "premium" members of AF archery's lineup. Clear glass laminations, bamboo core, etc. A beautiful bow, full disclosure though this one shipped with a string too long for it. Twisting a string can reduce its length, however the amount of twist required in this case also has the possibility of inducing "stretch" thus robbing performance.

FORCE DRAW DATA

This is simply the force required to draw a given bow the listed distance. It gives you a basic look at how the draw of the bow goes, notably smoothness. At the bottom, we listed two metrics in an attempt to empirically compare stacking. They are the slope of the F/D curve in the last two inches, and the percentage of the bow's total poundage gained in the last two inches. The slope of the F/D curve is typically a reasonable indicator and comparator between bows of similar design and poundage, however as the Hwarang clearly demonstrates bows with a greater overall poundage are destined to have steeper slopes as they simply need to gain more ground over the length of their draw.

STORED ENERGY DATA

This data set is, at its essence, the integral of the force draw curve. You're simply looking at a bow's ability to store energy. This represents your total energy budget with which to propel an arrow. Firing an arrow of hypothetically infinite mass, you would impart this amount of energy to it. More is better, hypothetically anyway, but what is the cost of this energy storage?

STORED ENERGY/POUNDAGE

Stored energy divided by poundage at that distance. Simple concept, but what does it mean? In essence, you're looking at the adjusted price (per pound cost) of storing energy in a bow. Quite simply, higher is better because you're getting more stored energy for the poundage you have to hold. Bows with higher brace heights and bows which stack at the end of their draws tend to suffer here because the former store less energy and the latter spike late at a higher poundage.

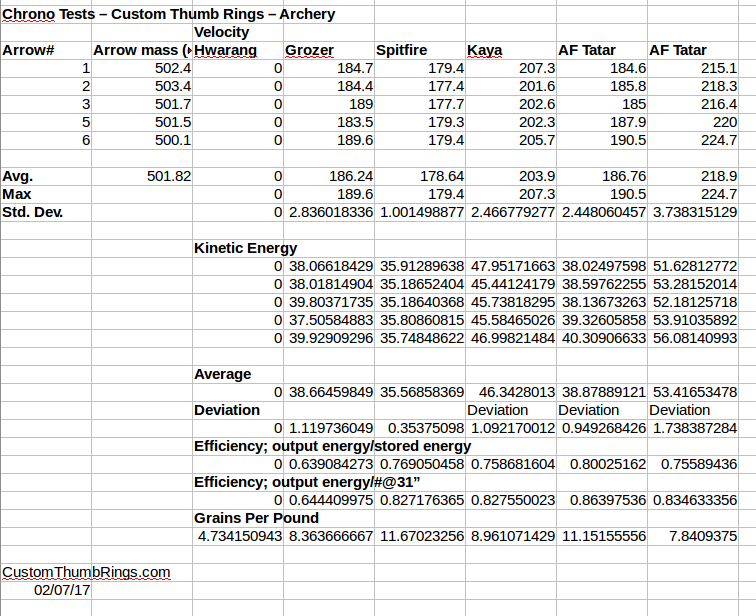

CHRONO AND EFFICIENCY DATA

This is really where the rubber meets the road. How fast is an arrow spit, how efficiently does a bow use its stored energy, and how light an arrow can you safely shoot? Different manufacturers have their own cutoffs, and it is worth asking yours for this number, but when people talk about minimum grains per pound (GPP) and minimum safe spine, this is what they're talking about. All the energy you store in that bow has to go somewhere, and that which doesn't go into the arrow has to be re-absorbed by the bow. The faster the bow has to move to propel an arrow, the more energy it must expend and subsequently reabsorb accelerating itself, rather than the arrow. This is why flaccid arrows, or lightweight arrows, tend to be less efficient. This efficiency number varies greatly by bow. Lighter laminated bows tend to be more efficient, but also more delicate. Solid fiberglass bows tend to be less efficient, but without a core to fatigue and fail they tend to tolerate absorbing more energy. My personal rule of thumb, is that laminated bows should run above 70% efficient and solid fiberglass bows above 60% efficient for their own safety, however in virtually all cases you'll experience rather startling hand-shock unless you operate above somewhere around 70%. Laminated bows which require greater than 75% efficiency to operate safely according to the manufacturer, as a general rule, I try to avoid as it indicates a design in need of reinforcement. Again though, these are my rules of thumb, not hard and fast rules, so please take all of this with a grain of salt. And, of course, hypotheses like this are always subject to change.

Why are there more bows in the stable than are listed here? Well there are a variety of reasons. The short version though is that only certain times of year, due to temperature, are conducive to testing bows. Furthermore, we like to keep things fair and balanced. Given fixed mass arrows, some bows such as the Hwarang are not necessarily safe to even test with such light arrows and even if we did it would unfairly handicap the bow. Not to mention >100# spined arrows are hard to come by. The solution to this is to be determined. We will add to this list as time and conditions permit.